"Get me in a voting booth": Tales of Jim Crow Montevallo

At the height of the Jim Crow era, in the 40s, 50s, and early 60s, African Americans who could afford to travel routinely consulted the Green Book, a travel guide offering "Assured Protection for the Negro Traveler." It told folks where they would be welcome and where, by implication, they might encounter hostility and even violence. Entries for friendly establishments in Alabama were scant. Travelers could expect "Food & Rest" in Birmingham, churches of all denominations in Mobile, and a safe service station in Huntsville. But Montevallo? Not a single establishment made the Green Book listing.

Stories of hardships in Montevallo during the Jim Crow days still circulate in the Black community. "It was a life of segregation of course," recalled Barbara Belisle, and "there were signs all over town 'colored' 'whites only,' things like that." Some remember having to let white people get in front of them in a line, no matter how long they had been standing there. Of having to stand on the bus even when traveling to Birmingham to have a painful leg injury treated. Of collecting orders at the back door of a restaurant or the side window of the Dari-Dee. Of having to wait for school busses that may or may not show up to get to them to the ill-equipped negro elementary school in Almont.

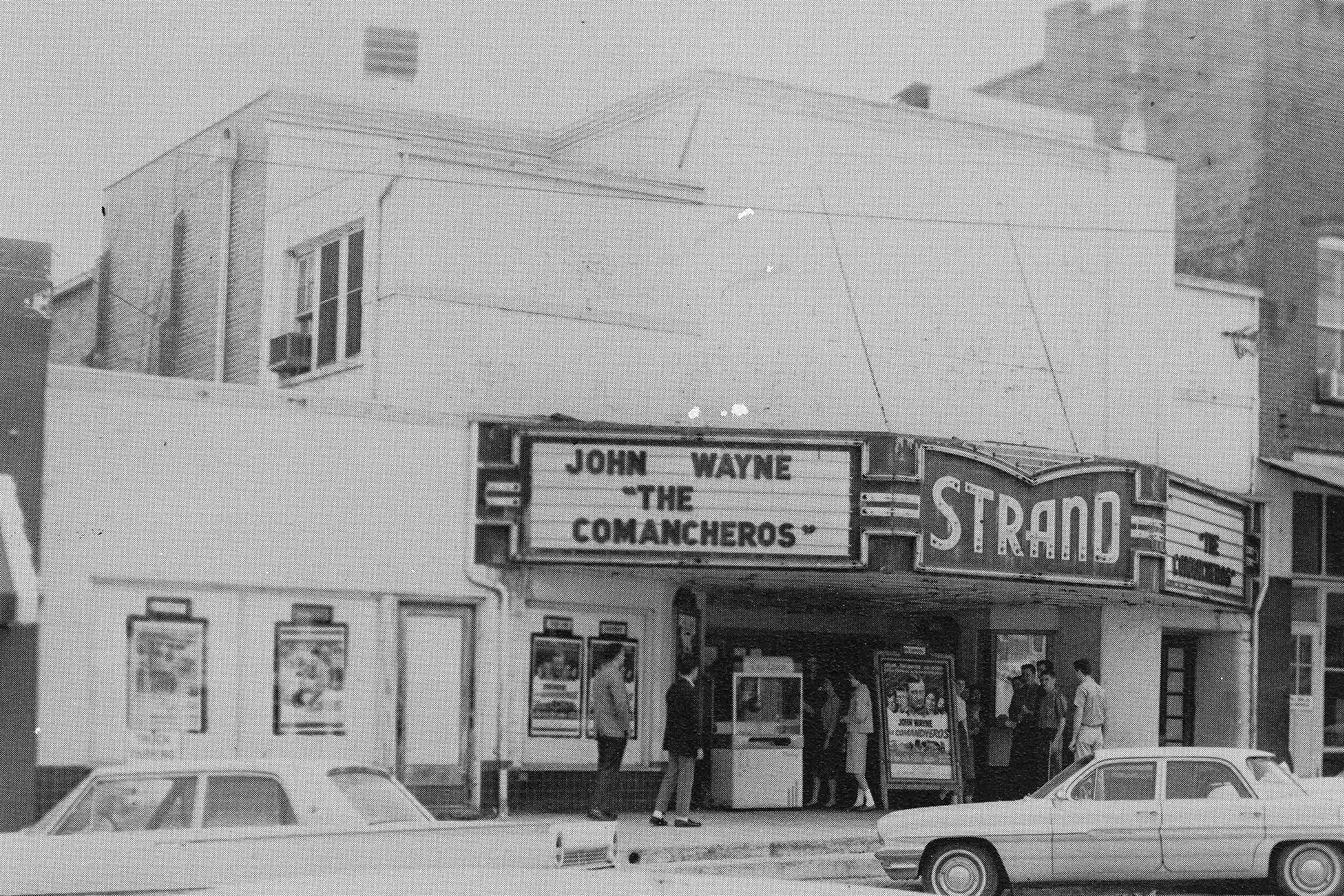

But you can also hear stories about defeating the absurdities of Jim Crow. At the Strand movie theater Blacks had to enter through a separate door and make their way upstairs to the colored balcony. (When he came to town in 1965 enroute to a voting rights march in Selma, Andrew Young, future Atlanta mayor and Ambassador to the UN, sat with his wife in the balcony.) The Strand "had no restroom for 'colored'," so "we had to go outside in back of the theater behind a tree -- night or day," recalled Belisle. Her younger cousin Vanessa Cottingham laughingly remembers the bathroom situation. "Until I was a teenager I didn't even know that the theater had a bathroom or a lobby in the bottom section." But instead of using the tree out back, "we could at least run up to City Hall and go to the bathroom there."

Jim Crow craziness may have kept them from buying treats in the lobby and availing themselves of the indoor plumbing but Black kids would not be robbed of their pleasures. They brought their own candy and popcorn, made their way to the tree out back or to City Hall to relieve themselves, and doubtless had good times in the balcony, where, it was said, they enjoyed a better view than the white patrons downstairs.

Still, the Jim Crow system was hurtful and deeply unjust. Local civil rights activists in the 60s such as Rev. Albert Jones, Rev. Earnest E. Vassar, and Leon Harris Sr. began to insist that the white establishment live up to the nation's promise of justice and equal rights for all. Voting rights became a huge issue. News of the cross-burning in Rev. Jones's front yard, thought to be the work of the police, provoked an indignant response from Leon Harris: "Police supposed to

be protecting all the citizen," Jones quotes him as saying; "now they're going to do a thing like this, put a burning cross in a citizen yard. Get me in a voting booth."

Rev. Vassar managed to get himself registered to vote by 1962. Barbara Belisle helped her father, William Mayweather, prepare for the notoriously unfair "literacy test" that blocked much of the Black vote. "I remember helping him memorize portions of the Constitution so he could recite them to a person who would let him register to vote -- or not. I can't remember how many times he tried before they let him register." But he kept going back. Aided by his daughter and his own resolve, Mr. Mayweather secured the right to enter a voting booth.

Strand Theater in the early 60s. The recessed door on the right led to the colored balcony.

In his oral history Rev. Jones details his experience of registering to vote at the courthouse in Columbiana when he returned from military service in the mid-60s. For starters, he had to provide names of white people who could vouch for him. Next came payment of the poll tax. He produced a twenty dollar bill, more than enough to cover the $2.50 tax, but was told he would have to go to a store for change. To a chorus of laughter, as he headed for the door, one of the white men "started spraying behind me." (Lysol Disinfectant Spray was first marketed in 1962). He returned with the correct change. Next, the infamous literacy test. He was ready and eager to begin: "Yes, sir. I know how to read and write." But first he would have to go back to the store to buy a pen, even though, as he pointed out, there's a "stack of pens in the little ole cup there." "These white folks pens." So off he goes, and again the spraying behind him. More petty harassment ensued but he was finally able to take and pass the test. The Rev. Jones, now a registered voter, was subjected one last time to the spray treatment. "Every time I leave out, he spray behind me. It was kinda . . . really sickening."

Montevallo was not listed as a safe place for the "Negro Traveler" in the Green Book. Humiliations and indignities were a feature of daily life in our town in the Jim Crow days, but the Black community stayed strong. The courage, resolve, and resourcefulness of African Americans of those days is a legacy we can all celebrate today.

Sources: We relied on oral history interviews preserved in UM's Milner Archives and Special Collections and a StoryCorps interview available online via PBS.

Contact us at MontevalloLegacy@gmail.com. We want to hear your stories and welcome correction of any errors of fact or interpretation.