Nero and Lidia King: a tale of thrift, oats, and freedom in Montevallo, Alabama

Ed. Note — Based on an account that first appeared in the Montevallo Chamber Chatter, this version supplies additional details about sources and personal histories, silently corrects a few errors in the earlier version, and prefers Lidia to Lydia as the way she may have spelled her own name. The following account of two former slaves in Alabama--enslaved persons is a more accurate description--casts a valuable light on Black life in the South after the Civil War.

It is rare to find details about Montevallo residents who endured slavery and went on to flourish in the post-Reconstruction era as free people. Rarer still when these details point toward a rich life story with layers to be teased apart and pondered. Such is the case with Nero and Lidia King--a perfect offering for Montevallo's Black History Month.

Nero King "commands the respect of all who know him," according to an 1888 newspaper account. His wife, an "old colored woman, well known as Aunt Lidia King," was a "land mark in this community" (Montgomery, Weekly Advertiser, Ap 5).

Nero was born in Georgia around 1808, probably to a woman enslaved by wealthy planter Edmund King, who would settle in Montevallo in 1817. A federal census return identifies Nero as mulatto, suggesting the possibility of white paternity. The child of an enslaver born of enslaved woman counted as "increase"--that chilling word is used in legal documents--and so remains property. Such was the greed that sought to maximize every financial benefit that could be squeezed out of the morally repugnant slavery system "peculiar" to the South.

Nero's owner died in 1863. Nero enters official records as part of the legal rigmarole that accompanies transfer of property when a slave-holder dies. Alabama law required that Edmund King's personal property be sold at public auction, the proceeds to be divided among his heirs. A record of this sale--including names and ages of the persons he enslaved--can be studied in the Shelby County Museum and Archives in Columbiana, Alabama, Will Book H, 1856-1867.

Nero was purchased by French Nabors for $1,400. Therein lies an untold story to which we shall return.

For now, note the irony that when Nero was put up for sale he had already been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. News travels slowly in Alabama.

The Emancipation Proclamation signed by Lincoln January 1, 1863 declared that enslaved persons in the Confederate States were free. Edmund King died June 28, 1863 and his personal property, including 29 enslaved persons, was sold at auction Dec. 21-23, 1863. At time of sale, Nero was aged about 56. See Will Book H, Shelby County Museum and Archives.

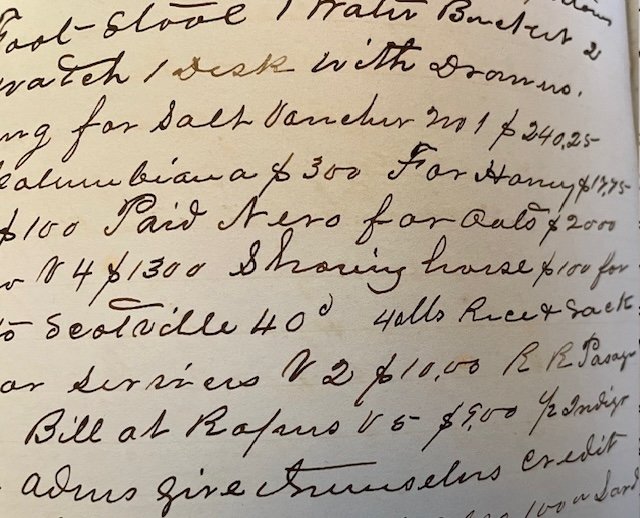

“Paid Nero for oats $2000.” From Will Book H, 1856-1867, Shelby Co Archives, Columbiana, AL.

Easily missed in the lengthy handwritten probate records is the provocative detail that Nero is named as one of King's creditors. "Paid Nero for oats $2000," the executors recorded. This is no inconsiderable sum, by the way, although by this time Confederate dollars had little value outside the South. (Exhibit "A," copy of Inventory filed July 8, 1863, Will Book H, p. 866.)

This detail may tell us something about Nero's work ethic, initiative, agricultural skills, and knowledge of grain cultivation. Obviously he had arranged with the landowner to sell the oats on his own account. Many plantations throughout the South allowed and even encouraged small gardens tended by enslaved persons, growing for their own use peas, corn, and the like. Nero's agricultural endeavors went well beyond gardening, however. He was in business for himself and his family.

Historians agree that Confederate demand for white male soldiers altered power relations between owners and owned. Some enslaved persons ran off; others did more farming on their own behalf. "Little wonder that some wartime slaveholders ultimately offered their slaves small wages or shares of the crop to keep them at work and the operations afloat" (Hahn, 15). Whatever Nero's arrangement with King, his executors regarded it as legally binding.

See Steven Hahn,

A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration

(2005).

This is the epic story of how African-Americans, in the six decades following slavery, transformed themselves into a political people—an embryonic black nation. Hahn demonstrates that rural African-Americans were central political actors in the great events of disunion, emancipation, and nation-building.

Nero and his wife Lidia (Lydia, Liddia, Lidie) emerged from slavery reasonably well-off considering they had lived their entire lives in bondage, a feature of Black life in the South after the Civil War that sometimes goes unreported. The 1870 census indicates they had real estate valued at $260 and personal estate at $100. (In today's dollars, $6,262 and $2,408.) According to the 1870 Federal Agricultural Schedule, they avoided the financial perils of sharecropping by renting outright 38 acres of improved land, including 22 acres of Indian corn and 15 acres of cotton. Livestock included two dairy cows, 10 pigs, and 4 chickens.

Nero was quick to exercise his newly acknowledged citizen's rights. He registered to vote at first opportunity in July 1867, in accordance with the Reconstruction Act passed in Congress in March of that year.

In newspaper accounts it is thrifty Lidia who steals the show. The Weekly Age-Herald (Feb. 27, 1889) tells the story like this: "When Edward [Edmund] King died his personal property was sold at public sale, and Uncle Nero was put on the block. His wife, who had been very thrifty, had saved up several hundred dollars, and with that money bid her husband in, thus securing his freedom, while she remained a slave." In The Weekly Advertiser account, the "unusually thrifty" Lidia "saved up nearly a hundred dollars in gold" which she exchanged for $15,000 in Confederate money. At the public outcry, she "bought her husband's freedom."

Lidia King may have earned money as a midwife while still enslaved. The 1863 King estate papers note that the executors "Paid Lidia for Midwifery $800" (Will Book H, p. 864.) Lidia had been owned by the Pitts family. In 1880 the King household included 13-year-old granddaughter Della Pitts.

The bill of sale in the Shelby County archives tells a more complicated story. Nero was not purchased by his wife but by one of the executors. As an enslaved person, she could not own property. Her husband was not exactly a free man, in other words, since legally he belonged to French Nabors. Nabors evidently acted on Lidia's behalf--in exchange for her family's lifetime savings--with support of the King family, who, as one paper puts it, "had such a kindly feeling for the couple that they would not bid against her" (Weekly Advertiser).

Trust in the "kindly feeling" of Nabors and the King family was never really tested. With the Surrender just a year and a half later, Nero and Lidia King truly gained their freedom.

Much of the information about these two former slaves in Alabama comes from Bill of Sale of Personal Property of Edmund King, Will Book H, 1856-1867, Shelby County Museum and Archives, Columbiana, AL. We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the Albert Baker Datcher, Jr. Enslaved Peoples Database hosted by the Shelby County Historical Society.