“I wasn’t afraid”: the Suburban League and the fight for equity in Montevallo, Alabama Pt. 2

“The Suburban League has helped a lot of people, known and unknown.”

The story of Sarah Lacey and the Food Center shows the rippling effect of local acts of courage. The Suburban League’s success in turning little Montevallo into an Alabama civil rights city relied on the strength of women.

A full accounting of their contributions may never be known. But we can be sure that female “soldiers” extended the League’s impact by offering food, clerical support, emotional care for families in crisis, a listening ear, even a steadying Black presence in jails and hostile courtrooms.

Women stepped into situations that required bravery—as was required of Sarah Lacey in 1970, when she stepped up to be the first person of color to ring up groceries in Montevallo.

Another woman of courage, Ethel Mae Thompson, recently reflected on her experiences as a “soldier” in the League. Her memories, combined with those of Ms. Lacey, help us understand the crucial role played by women in the day-to-day operations of Montevallo’s Suburban League.

Ethel Mae Thompson, portraying Harriet Tubman for ‘Black History with an Alabama Accent’

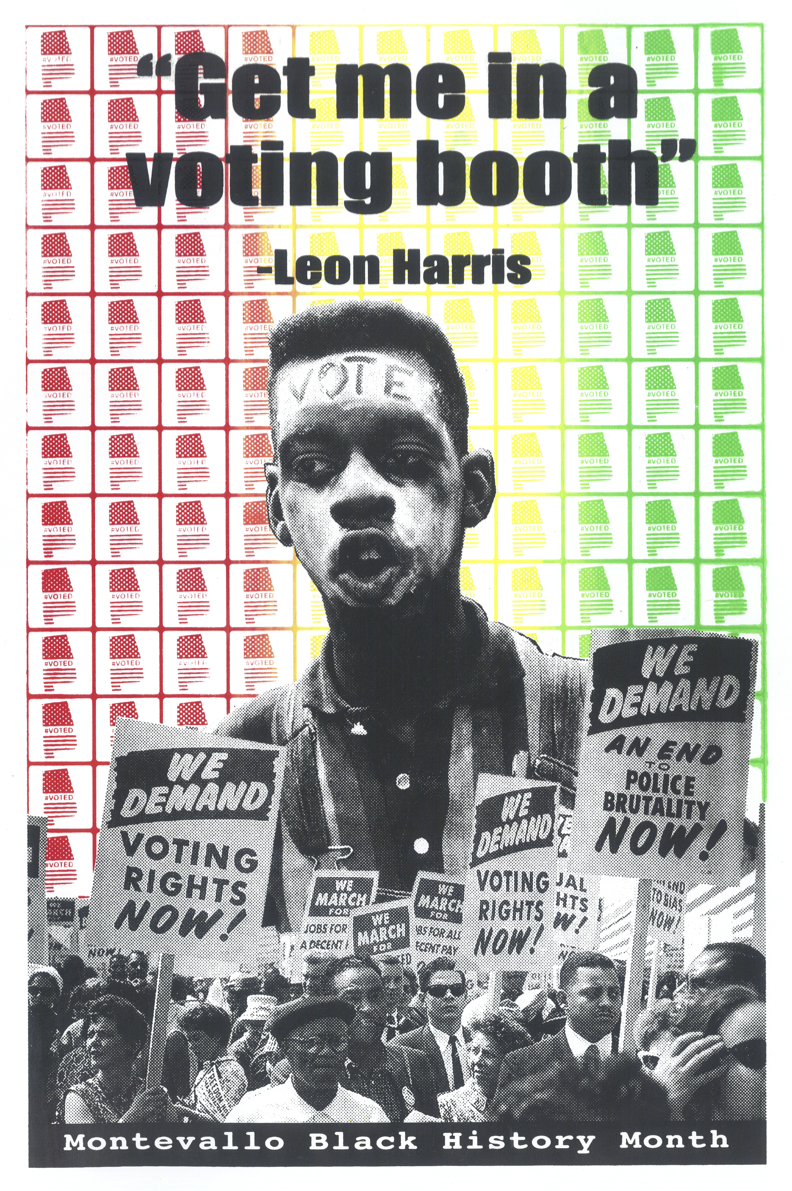

Banner designed by Adrian Mayton for a Black History Month art project at Montevallo High School

The core leadership of the League emerged from within a cadre of tried and trusted community leaders. They were pastors, deacons, Prince Hall Masons—activists who knew how to work collectively and strategically behind the scenes. Most had ties to churches and fraternal groups. Leon Harris, Rev. Albert L. Jones, and Rev. Eugene Vassar were among the League’s most visible leaders. They confronted city hall, school administrators, and police. They demanded voting rights.

“Get me in a voting booth,” Leon Harris once said, and his friend Rev. Jones did just that, challenging bigoted voting officials in Columbiana, as seen in an earlier Untold Story.

A key to the League’s impact was its strategy of collective action with maximum discretion. Plans were rarely discussed outside the inner circle until ready for execution. In rural Alabama, intimidation and violence were ever-present threats. A fraught confrontation with a public school official resulted in a cross-burning in front of Albert Jones’s house on Almont’s main thoroughfare.

Ethel Mae recalls that male leaders recruited women—and sometimes their own children—for carefully planned tasks. It was Clifton Lacey, Sarah’s father-in-law, who encouraged his daughter-in-law, just out of high school and recently married, to take the cashier job at Moss’s Food Center.

“It was the children who got us our freedom. The adults had to be cautious—they had too much to lose.”

Women soldiers fought on behalf of other women who lost ground in the wake of desegregation. When cafeteria staff were consolidated in the early 1970s, longtime employees like Eunice Haggins and Polly Salter lost pay and status. Ms. Salter, previously a supervisor at Prentice High, was demoted to the bottom rung at the newly integrated middle school.

Women of the League joined the fight for fairness, demanding better wages and job titles for justifiably angry food service workers.

Polly Salter is in the middle of the top row. Photograph contributed by James Salter.

Ethel Mae credits her church—Ward Chapel A.M.E.—and leaders like Rev. Dwight Dillard and Leon Harris for her involvement in the League. “They encouraged everybody,” she says, “but some they was just really after.”

They were really after Ethel Mae. Why her? A long pause. “I wasn’t afraid.”

The League was a male-led organization. Planning often took place in the Masonic Hall, discreetly located on a cul-de-sac behind Shiloh Baptist Missionary Church at 160 Commerce Street. (The hall, presently home to Stone Mountain Lodge #187, now bears a historic plaque.) Strategy sessions might continue late into the night at Leon Harris’s house across the street.

The brothers of Mason Hall, featured on the Montevallo African American Heritage Trail.

But women of the community were unwavering in their resolution and support. “The men was the officers. And once they got it together, they reached back and needed a few soldiers,” Ethel Mae recalls. She was one of the chosen: trusted to stay quiet, do the work, and get the mission done.

Some may regret the male-dominated structure of the 1970s Suburban League, but we prefer to emphasize its collective spirit. The League was many things—a self-help society, an organ for civil rights advocacy, a protection society. Ordinary folks, including Black women and youth, worked together to make life a little better for kin and community. It was never just a handful of male leaders—it was a collective effort, with fearless women on the front line.

Our thanks to Ethel Mae Thompson for sharing her role in a campaign that transformed little Montevallo into an Alabama civil rights community in an interview recorded May 27, 2025. Do you have information that adds to our knowledge of the Suburban League? We would love to hear from you at Montevallolegacy@gmail.com.